When an employee announces she’s pregnant, her employer better be able to deliver more than just congratulations. You need legally sound, consistent policies and practices to ward off potential pregnancy complications of your own.

It’s important to know what you must do—and what you can’t do (or say)—under federal anti-discrimination and leave laws. Plus, it’s vital to understand your own state statute, which may provide more liberal leave benefits for pregnant women and new parents.

While no federal law requires you to provide paid maternity leave, most employers must comply with the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) and the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). And even the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) may come into play if pregnancy complications rise to the level of substantially limiting a major life activity.

Here’s how best to comply with those laws, plus a sample policy you can adapt to your own organization.

The PDA prohibits discrimination against employees and applicants on the basis of “pregnancy, childbirth and related medical conditions.” Any employer that’s subject to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (i.e., has 15 or more employees) must comply with the PDA.

Under the law, you can’t deny a woman a job or a promotion merely because she’s pregnant or has had an abortion. Nor can you fire her because of her condition or force her to go on leave as long as she’s physically capable of performing her job.

In short, the law requires you to treat pregnant employees the same as other employees on the basis of their ability or inability to work. That means you must provide the same accommodations for an expectant worker that you do for any employees unable to perform their regular duties. For example, if you provide other work for an employee who can’t lift heavy boxes because of a bad back, you must make similar arrangements for a pregnant employee.

Caution: Employers that use light-duty programs to cut workers’ compensation costs often make one big legal mistake: They haphazardly apply their policies, allowing some employees to take light-duty jobs, but not others. That inconsistency is the fastest way to trigger discrimination lawsuits from employees who may need light-duty positions temporarily for other reasons, such as pregnancy.

In addition, the PDA requires you to provide sick leave and disability benefits on the same basis or conditions that apply to other employees who are granted leave for a temporary disability. Women who take maternity leave must be reinstated under the same conditions as employees returning from disability leave.

At the same time, you’re allowed to apply the same requirements that you impose on other employees. So, if you usually require employees to obtain a doctor’s note before allowing them to take sick leave and collect benefits, you can impose the same rule on pregnant employees.

Other key PDA provisions:Advice: Charges of discrimination on the basis of pregnancy or related conditions are difficult to fight in court. You will lose unless you can clearly prove that the reasons for not hiring or for discharging the plaintiff were unrelated to her pregnancy.

Two cases in point:1. A sales manager for a telecommunications company secured a lucrative contract in Eastern Europe under which she would be paid a percentage of all sales. But before the products were shipped, she announced she was pregnant. She was terminated almost immediately with no reason given. She sued under the PDA, Title VII and several state laws. A jury awarded her $98,364. The employer lost the appeal. (Houben v. Telular Corp., 231 F.3d 1066, 7th Cir., 2000)

2. A secretary at a real estate company was terminated while on maternity leave. During that time, her employer was experiencing financial problems, made several staff cutbacks and later filed for bankruptcy. The plaintiff sued under Title VII and New Jersey ’s anti-discrimination statute. Both the Bankruptcy Court and the District Court found in favor of the employer and held that she was terminated for legitimate, nondiscriminatory reasons. The 3rd Circuit affirmed the decision, saying the reason for her firing was the plaintiff’s work record prior to taking maternity leave, not the pregnancy. (Rhett v. Carnegie Ctr. Assoc., 129 F.3d 290, 3rd Cir., 1997, cert. denied, 524 U.S. 938, 1998)

Tell managers: Mum’s the word

Singling out pregnant employees for any reason can lead to a lawsuit. If supervisors make little jokes about pregnancy and childbirth, rein them in.

In one recent case, when a top performer received an award at a luncheon, she was taken aback when her boss casually said, “You’re not gonna get pregnant now, are you?” As luck would have it, she did become pregnant the following month. Then her boss began calling her “Prego” and soon was criticizing her work. She complained to HR, but the company didn’t investigate. She sued, and the court concluded calling her “Prego” and making comments about pregnancy amounted to a hostile environment. (Zisumbo v. McLeodUSA Telecom, No. 04-4119, 10th Cir., 2006)

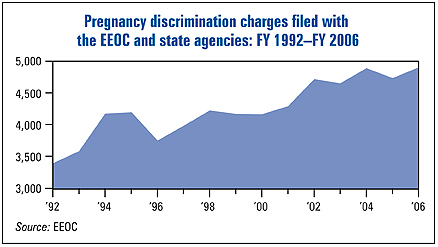

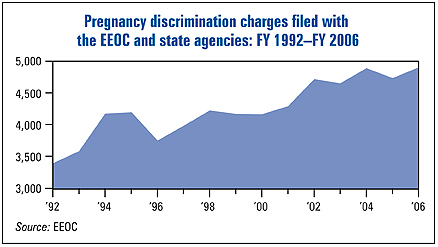

Caution: In FY 06, the EEOC received 4,901 charges of pregnancy-based discrimination, a 30% increase over the number of complaints filed a decade ago. (See graph below.)

When an employee becomes pregnant, her employer must also consider her right to take leave under the federal FMLA. Eligible employees can take up to 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected FMLA leave for the birth, adoption or foster care of a child; caring for a child, spouse or parent with a serious health condition; or convalescence after an employee’s own serious health condition.

To qualify for FMLA leave, an employee must have worked for the same employer for at least 12 months (not necessarily continuously) and clocked at least 1,250 hours of service (slightly more than 24 hours per week) during the 12 months leading up to FMLA leave.

Any organization with 50 or more employees working within a 75-mile radius of the work site must comply with the FMLA.

New parents—both mothers and fathers—can take FMLA leave any time in the first 12 months after a child’s arrival. But employees must conclude their leave before the 12-month period ends. Presumably, the idea is that if a working mother takes her 12 weeks and then returns to work, the father can care for the child for the next 12 weeks.

What if both parents work for the same company? They’re entitled to a combined total of 12 weeks’ leave after the birth or adoption. In this case, each parent would have the difference between 12 weeks and the amount of leave they took for the child to use for any other legitimate FMLA reason in that year.

Example: Bob and Linda Jones have a child and work for the same employer. Bob takes four weeks’ leave, and Linda takes eight weeks’ leave for their child’s arrival. Bob still has eight weeks of leave to use in that year for any other FMLA purpose; Linda has four remaining weeks.

‘Serious health condition’

Keep in mind that employees can also use their allowable FMLA leave if they suffer complications during pregnancy or prenatal care that constitute a “serious health condition.” (The FMLA defines a “serious health condition” as “an illness, injury, impairment or any physical or mental condition that requires inpatient medical care or continuing treatment by a health care provider.”)

Case in point: Cindy Hiemer said her chronic lung problem was exacerbated by her pregnancy. She asked her employer, Anthem Insurance, for FMLA leave. After she was fired for failing to call in sick, she sued the company, alleging interference with her right to FMLA leave. But Anthem Insurance said her absence wasn’t a serious health condition—Hiemer had testified she couldn’t come to work because she was nauseous and lightheaded. The company said FMLA didn’t cover that sort of problem.

The court disagreed, concluding that—since FMLA regulations say anything related to pregnancy automatically qualifies as a serious health condition—nausea and lightheadedness might be enough. The case now goes to trial, and Hiemer will get a chance to convince a jury her absence was pregnancy-related. (Hiemer v. Anthem Insurance Companies, No. C-1-05-124, SD OH, 2007)

Advice: When it comes to a pregnancy, employers may want to follow the safest path: Approve any absences that are even remotely related to the pregnancy as FMLA-covered time off.

Reasonable accommodation under the ADAA normal pregnancy is not considered a disability under the ADA . The law defines a disability as “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.”

But if a woman experiences pregnancy complications that substantially limit a major life activity, she may be considered disabled under the ADA and, therefore, entitled to reasonable accommodation to perform her job.

Example: If a new mother is still unable to return to work after exhausting her 12 weeks of FMLA leave, you should evaluate her condition under the ADA to determine whether additional time off is a reasonable accommodation for her. (Also, be sure to check your state law because some states provide more than 12 weeks of parental leave.)

All employers that have 15 or more employees must comply with the ADA.

Check your state law

Several states mandate more generous maternity and family leave than the FMLA (and some state laws apply to smaller employers). Here are a few examples:

California ’s provisions on pregnancy disability leave cover employers with as few as five employees. The leave is capped at four months. But it’s important to note that pregnancy disability leave comes in addition to leave taken under the California Family Rights Act (covering employers with 50 or more employees). So, an employee covered by both laws could in effect take four months of pregnancy disability leave and then 12 weeks of family leave to care for a new child.

Tip: You can access more information on state leave laws on the National Conference on State Legislatures’ site: www.ncsl.org/programs/employ/fmlachart.htm.

Not many employers choose to offer paid maternity leave aside from what’s covered in their short-term disability policies.

In the 2007 Benefits Survey by the Society for Human Resource Management, 81% of the HR professionals polled said their organizations offer short-term disability benefits. But only 18% said they have a separate, paid maternity leave policy (compared to 14% in 2003). Also, only 17% said they provide paid paternity leave (versus 12% in 2003). Even though the number of organizations that provide paid time off remains small, it’s noteworthy that more of them are offering paid paternity leave these days.

It’s also up to each employer to decide how many weeks of paid leave to offer. For example, one accounting firm with an 80-person staff provides new moms and dads who are full-time employees 30 days’ paid leave and an additional 60 days’ unpaid leave upon the birth or adoption of a child. By contrast, a large broadcasting corporation gives moms with one year of service eight weeks of paid maternity leave on top of two weeks of paid pre-maternity leave, while new dads get two weeks’ fully paid leave.

If you decide to adopt a formal maternity/paternity leave policy, make sure it complies with federal and state regulations. Since some state laws grant employees more generous leave and may apply to smaller employers than the FMLA, make sure your attorney reviews your policy before you disseminate it to employees. (See sample policy in box below.)

Here’s sample policy language that you may want to adapt to your organization’s needs, subject to review by your attorney:

[Your organization] is firmly committed to protecting the rights of expectant mothers and complying with Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act as amended by the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978. [Your organization’s] policy is to treat women affected by pregnancy, childbirth or related medical conditions in the same manner as other employees unable to work because of their physical condition in all employment aspects, including recruitment, hiring, training, promotion and benefits.

Further, [your organization] fully recognizes eligible employees’ rights and responsibilities under the Family and Medical Leave Act, applicable state and local family leave laws, and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Paid leave may be substituted for unpaid maternity leave in accordance with [your organization’s] paid-leave substitution provisions of [your organization’s] FMLA policy.

Pregnant employees may continue to work until they are certified as unable to work by their physician. At that point, pregnant employees are entitled to receive benefits according to [your organization’s] short-term disability insurance plan.

When the employee returns to work, she is entitled to return to the same or equivalent job with no loss of service or other rights or privileges. Should the employee not return to work when released by her physician, she will be considered to have voluntarily terminated her employment with [your organization].